You Are Not Stephen King

There’s an Apple productivity blogger and podcaster named David Sparks, who seems sincerely to have all his shit tied up neatly, as far as personal and professional productivity systems go. The impression one gets is that just by waking up in the morning, he sets off an automated chain of scripts and shortcuts that glide him, digitally speaking, through his day. He’s a wonder of the worldwide web.

If you are not like him, it can be frustrating, expensive, and emotionally thorny to follow too closely the advice of someone like David Sparks. He has dotted every i. I barely fold my Tees. (David Sparks would never permit himself such a doddering pun, probably, for instance.) Many hundreds of dollars have I spent trying to be more like David Sparks in how I work. It hasn’t all been a waste, not nearly — I still use plenty of the hardware and software and insights that he evangelizes — but, over the years and from time to time, I have taken his ideas too much to heart and, when I have, I have always fallen many miles, whole continents short. There are 31,134 unread emails in my email inbox, and if that number ever goes down, it will be with a bulldozer, not a scalpel.

Stephen King’s book On Writing is a contender for most-often mentioned book on the process of writing, tied perhaps with Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird. (For my money, the best book about writing is Audition by Michael Shurtleff, which is also the best book on acting.) On Writing is easy to read but not always easy to have read. The central lesson of the book: to be a writer, you must reserve hours each day, go to your workstation, and write. Come what may. Write like you are an accountant showing up to do accounting. Put on your visor, pull the chain on your banker’s lamp, sharpen your Dixon Ticonderoga number two pencil, and get to work. Every day. For hours.

Here’s the thing: a writer must, absolutely must write like Stephen King… if they aspire to write like Stephen King. You simply can’t put out sixty-five books and two hundred short stories in fifty years without treating your job as a writer like you are an accountant.

But say, like me, you would be content to write and publish two or three really good books in your entire life, your process can look a lot more idiosyncratic.

There are two ideas that changed my life more than any others in terms of writing process. I’m no Stephen King, but I have thrown away more novels (about two and a half, when you add them up) than most people who want to write have written, and I’ve recently finished a third novel that I don’t intend to throw away, so I have some standing on the topic if not exactly any authority.

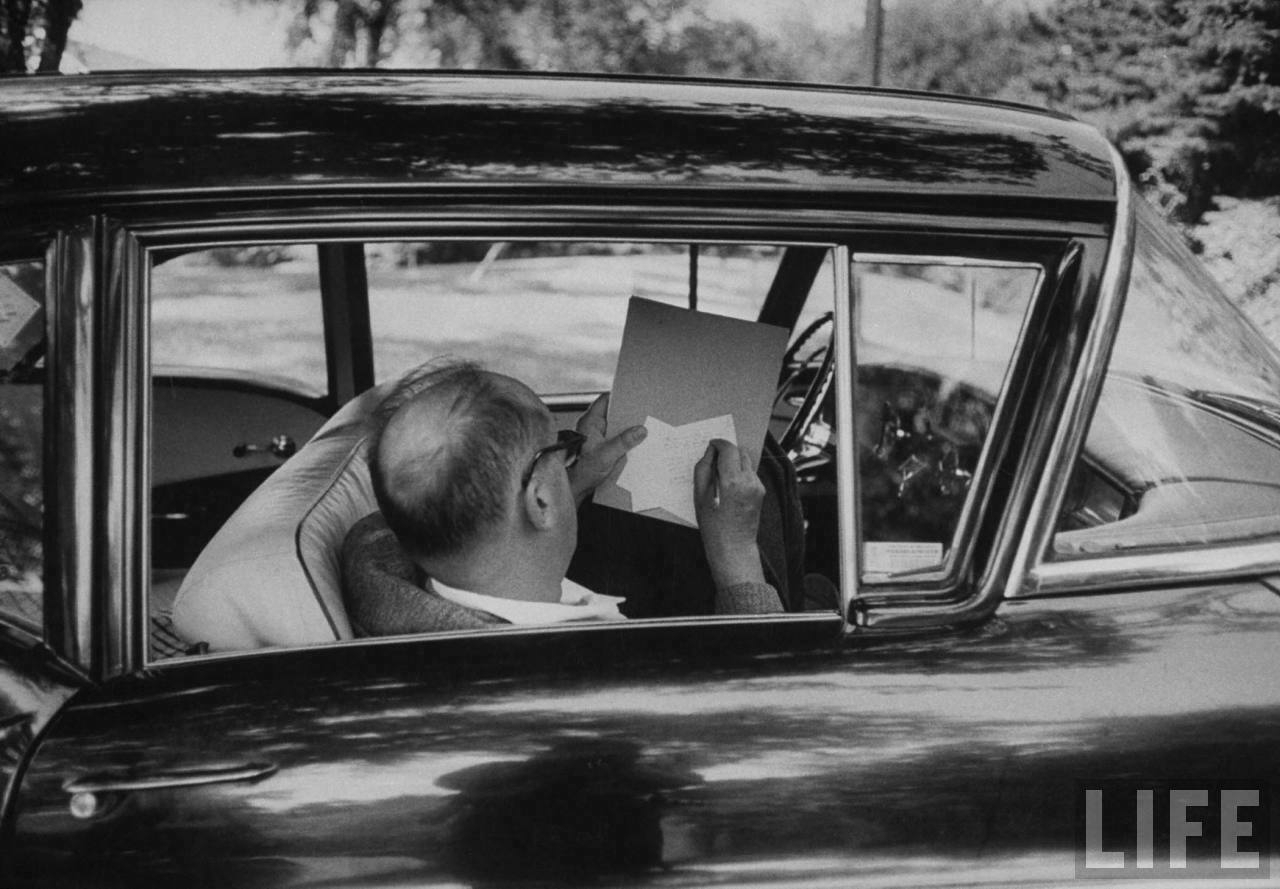

The first important idea is The Hipster PDA by Merlin Mann. For about ten years, I carried index cards in my back pocket. Those index cards have since become a series of applications on various electronic products made by Apple Inc., but the index card metaphor prevails. Writing on index cards, both literally and as a mindset, was the topic of my graduate thesis. Two of my favorite novels, Why Did I Ever by Mary Robison and Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill, were written on index cards. Nabokov, possibly the best regarded writer of English fiction of the middle portion of the twentieth century, wrote most of his novels on large index cards, sometimes in his car.

From my own thesis paper (I do not drive, but I get the appeal of an office on wheels):

The car is a portable, rearrangeable office, the way index cards are portable, pocketable paper. Both stand for practicality over preciousness. There is nothing romantic about either index cards or writing in a car. There is only so much fussing you can do with either.

For the practical writer, the car is an ideal room of one’s own, one which is sound dampened and which can be literally driven away from distraction. Index cards, about the size of the center of a steering wheel, are stiff enough to be their own clipboards when stacked.

The other important idea came from Angie Cruz, author of the fabulous and funny Dominicana. In a talk given to a class I was in, she described herself as a “binge writer.” My notes from that lecture follow that term with FIVE exclamation points. She, this writer of a book I both enjoyed and admired, described a writing process, and a writing cadence, that sounded like mine. Never every day, sometimes a ton all at once. She gave a few tips:

- Go with the way that works for you.

- Your art is your art.

- Set up systems of external deadlines and accountability.

It can be tempting to think that “productivity” (whatever that is) is the reward of a Puritanical reshaping of your soul. But, in my life, the best and most generative gains have come from giving myself permission to be who I am and to work as I work.