Archimedes

Archimedes

needed a

definitive spot to

rest his feet where from

earth could

ascend by his lever.

Who Cares

Smiles are tacky in

The winter, doldrums

Follow the dull drums

Of the holidays.

Daylight busts in

Interstitially. Catch

It or don’t. Who cares

But me, too much.

Visiting Mrs. Rakefield at the Hospital

Nothing Peggy says makes sense anymore. For instance, at the picnic, we’re all there in the park, the blanket, we’ve got coolers and tote bags. The blanket is coming up in the wind. Peggy has a couple of small bags, just enough not to attract notice about how little she’s carrying. But I notice. She sees the corners coming up on the blanket, and I swear what she says is

“Someone ought to do something about that.”

Now, Peg, last I checked, you’re someone, and in this case the only one not packed to the back like a mule. Not to mention the kids. She’s the only one left without one, that’s official, as of July with whats her name, Merrett’s kid. June.

Whatever, that’s just a small thing, anyone can lapse, but when I tell you Peggy is on one.

So here I am, trying to be a good friend, I’m going to visit her mother today in the hospital. Peggy’s mom, not someone I’ve kept in touch with, but she was nice to me in high school, and it’s been warm the couple of times I’ve seen her since, so I’m gonna say hi today.

This is no fun, being stuck on the bus. My car is in the shop, and Terry’s right, he needs the other one more than I do. Thankfully, he was able to take Whisper for the afternoon, for once, so I could do this visit.

The bus, woof. There’s an old lady on here, you would not believe the stink lines coming off this one.

“Should we get a table?” That was another one. Me and Peggy, a few weeks ago, just the two of us, getting dinner. No, Peg, I was thinking we could eat on the floor like a rat. Maybe they have some milk crates in the alley. We can eat like the dogs in movie with dogs who date.

It’s hard for me to take anyone seriously anymore since getting laid off.

Peggy’s mom is the kind of lady who will spend twenty minutes asking about you even though she’s the one in the hospital bed. I’m not at the hospital yet, I’m just saying.

The driver talks a lot but you can’t understand her words. I told her let me know when it’s my stop. She said I’ll be able to see the hospital from the bus.

“Ok,” I said. “But let me know when it’s my stop.”

I brought Kirkland trailmix because I know I’m gonna get hungry, and guess what, I’ve eaten it all already. That was return trip trailmix. I’m gonna have to eat hospital food.

Nothing, these days, is good enough for people. There’s a teen on her phone complaining about lifeguards. Not on the phone with anyone you understand, just talking into the phone looking at herself. No judgements, who doesn’t do that, but I mean the lifeguard stuff is putting me to sleep. Imagine how her friends feel, if she’s got them.

There it is, the hospital. The driver was right. I wait to stand up to see if she’ll say anything to me, but she doesn’t. She just yells “HOSPITAL” loudly and louder than the other stops and I can actually understand what she’s saying for once. That’s good enough, I guess. Just like me, scraping by.

After my last interview, Terry asked if I was toning it down for them. The guy has worked at the same job for fourteen years — what does he know about interviewing?

It’s a long walk to the entrance. You have to walk across the entire parking lot. The bus is the “cheap seats” any way you cut it.

They’ve got this big horseshoe entrance like we’re checking in at The Palms Resort instead of a death factory. Bile and blood and piss and shit, but look at this fancy entrance.

No line at check-in but, fuck me, did I forget to bring ID? I’ll grab a surgeons scalpel and slit my throat and wrists if I did. The bus is bad enough without not even getting in.

No, I’ve got my ID.

“Do you take Visa?”

This is the joke I make every time I’m checking in to a place. Good for a smile at least. If they think I’m corny, so what? I’ll take one on the chin to brighten someone’s day. No, I’m not a saint, but there’s no denying the ways I am saint-like.

The elevator takes long enough. Hospitals are often a million stories high, but I only get invited to the first twelve — figure that one out.

Floor six, Oncology. And boy does Mrs. Rakefield have a big one. You can see it, right as you walk in. What were they thinking, a big thing like that on her collarbone and nobody’s treating it until it’s that bad? Tumors aren’t Chia Pets, they take a while to get like that.

From Peggy, I’d expect it. But Mrs. Rakefield I thought was more with it. Apple doesn’t fall far, I guess. One point “nature.”

How wrong was I though? All she wants to talk about is the pain and the bordom. Ok, fair enough, we’re on her hospital time.

Boy, is she thankful I’m here though, good old Mrs. Rakefield. To think, she used to look so old to me when she was younger than I am, and now I’m older than she was. No, wait, that’s not right. But almost!

“Well, you know Peggy…” I say so something she said, I don’t remember what, just she mentioned Peggy and I wanted to change the subject.

“How do you mean?” she says. Now we’re playing twenty questions.

“She’s kind of a spectator,” I say. “Not in a bad way. Just she doesn’t always jump in.”

Mrs. Rakefield has to sit with this truth bomb for a while, but the bigger truth is she knows it and I know it.

Then guess who walks in — Peggy herself, holding some kind of donut pillow. I think it’s for the toilet, but it goes right behind her mother’s head.

“How are you holding up?” Peggy asks me.

Like she wants to know.

Visiting Mrs. Rakefield at the HospitalYou Are Not Stephen King

There’s an Apple productivity blogger and podcaster named David Sparks, who seems sincerely to have all his shit tied up neatly, as far as personal and professional productivity systems go. The impression one gets is that just by waking up in the morning, he sets off an automated chain of scripts and shortcuts that glide him, digitally speaking, through his day. He’s a wonder of the worldwide web.

If you are not like him, it can be frustrating, expensive, and emotionally thorny to follow too closely the advice of someone like David Sparks. He has dotted every i. I barely fold my Tees. (David Sparks would never permit himself such a doddering pun, probably, for instance.) Many hundreds of dollars have I spent trying to be more like David Sparks in how I work. It hasn’t all been a waste, not nearly — I still use plenty of the hardware and software and insights that he evangelizes — but, over the years and from time to time, I have taken his ideas too much to heart and, when I have, I have always fallen many miles, whole continents short. There are 31,134 unread emails in my email inbox, and if that number ever goes down, it will be with a bulldozer, not a scalpel.

Stephen King’s book On Writing is a contender for most-often mentioned book on the process of writing, tied perhaps with Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird. (For my money, the best book about writing is Audition by Michael Shurtleff, which is also the best book on acting.) On Writing is easy to read but not always easy to have read. The central lesson of the book: to be a writer, you must reserve hours each day, go to your workstation, and write. Come what may. Write like you are an accountant showing up to do accounting. Put on your visor, pull the chain on your banker’s lamp, sharpen your Dixon Ticonderoga number two pencil, and get to work. Every day. For hours.

Here’s the thing: a writer must, absolutely must write like Stephen King… if they aspire to write like Stephen King. You simply can’t put out sixty-five books and two hundred short stories in fifty years without treating your job as a writer like you are an accountant.

But say, like me, you would be content to write and publish two or three really good books in your entire life, your process can look a lot more idiosyncratic.

There are two ideas that changed my life more than any others in terms of writing process. I’m no Stephen King, but I have thrown away more novels (about two and a half, when you add them up) than most people who want to write have written, and I’ve recently finished a third novel that I don’t intend to throw away, so I have some standing on the topic if not exactly any authority.

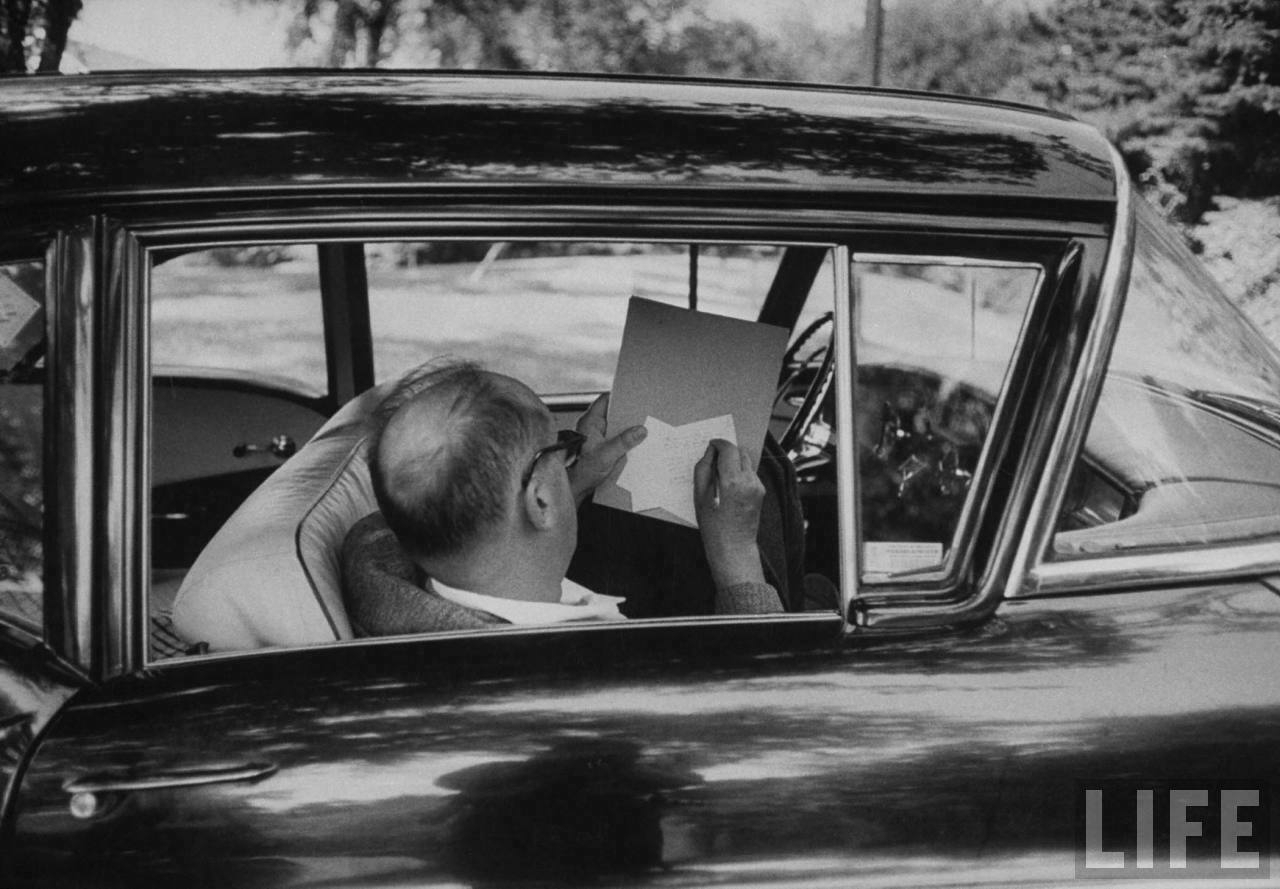

The first important idea is The Hipster PDA by Merlin Mann. For about ten years, I carried index cards in my back pocket. Those index cards have since become a series of applications on various electronic products made by Apple Inc., but the index card metaphor prevails. Writing on index cards, both literally and as a mindset, was the topic of my graduate thesis. Two of my favorite novels, Why Did I Ever by Mary Robison and Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill, were written on index cards. Nabokov, possibly the best regarded writer of English fiction of the middle portion of the twentieth century, wrote most of his novels on large index cards, sometimes in his car.

From my own thesis paper (I do not drive, but I get the appeal of an office on wheels):

The car is a portable, rearrangeable office, the way index cards are portable, pocketable paper. Both stand for practicality over preciousness. There is nothing romantic about either index cards or writing in a car. There is only so much fussing you can do with either.

For the practical writer, the car is an ideal room of one’s own, one which is sound dampened and which can be literally driven away from distraction. Index cards, about the size of the center of a steering wheel, are stiff enough to be their own clipboards when stacked.

The other important idea came from Angie Cruz, author of the fabulous and funny Dominicana. In a talk given to a class I was in, she described herself as a “binge writer.” My notes from that lecture follow that term with FIVE exclamation points. She, this writer of a book I both enjoyed and admired, described a writing process, and a writing cadence, that sounded like mine. Never every day, sometimes a ton all at once. She gave a few tips:

- Go with the way that works for you.

- Your art is your art.

- Set up systems of external deadlines and accountability.

It can be tempting to think that “productivity” (whatever that is) is the reward of a Puritanical reshaping of your soul. But, in my life, the best and most generative gains have come from giving myself permission to be who I am and to work as I work.

You Are Not Stephen KingParable for the Perpetuation of Intergenerational Trauma

So afraid of bogeymen, we have not noticed the monster we have become.

Parable for the Perpetuation of Intergenerational TraumaNo, Seriously, You Contain Multitudes

Instead of seeking consistency in yourself or others — because we’re made of countless parts and those parts have parts and all those parts are capable of relating to each other — try to find and nurture emotionally safe harbors where all those parts can, when and where and with whom appropriate, yell, scream, dance, smile, shoot milk out of their noses laughing, move like a dork, seduce, whimper, paint, fuck, cry, and all other manners of live.

No, Seriously, You Contain MultitudesIn Writing, Sensory Detail Serves Scenic Detail

Sensory detail for its own sake is boring.

Nobody can reconstruct precisely what a character looks like from an exhaustive sensory description, and also it doesn’t matter. It’s boring to read.

Sensory detail should always serve scenic detail. Build the scene, not the character or setting.

Sometimes building a scene entails building a character.

Many characters can be described in a memorable and vivid way using two or three explicit sensory details:

“The man with the red lapel pin walked like an upright chimp.”

Do you need to know the build of his nose? Do you care what color his eyes are?

There’s a misapprehension that more detail is always better. “Show don’t tell.”

How’s this as a replacement: “Paint more scenes.”

In Writing, Sensory Detail Serves Scenic DetailIt’s Too Late

Nice try, but just saying “late capitalism” doesn’t make it so. Most historical epochs aren’t labeled in real time. Maybe we are living in “late capitalism,” but I’d bet most deployers of that phrase don’t know that it was coined around or before World War I.

In 2013, I started a daily email newsletter that I kept up for about half a year. Then I quit because:

- 2013 felt “too late” to start an email newsletter.

- The analytics — seeing who opened and who didn’t, and who unsubscribed — discouraged me and corrupted my inherent interest in writing and sharing these short essays.

Analytics kill art, or at least they have killed mine any time I’ve had the displeasure of paying attention to them. Feedback, more generally, is a friend of art.

Good feedback helps an artistic work become more itself. Sometimes I’d get a reply — in person or by email — to a newsletter I wrote, and that was always an artistically nurturing experience, even if someone disliked or disagreed with something I wrote. This feedback encouraged me to keep making the newsletter and to make it more true to itself.

Analytics shape work into something else. There is some wonderful, entertaining, sometimes informative stuff (“content”) driven by analytics, and maybe analytics can have a place in marketing artistic work, but it’s difficult to see how work primarily driven by analytics can be called art.

As for being “too late,” I was obviously wrong. I was, in fact, early to the newsletter bandwagon. The horses had not yet arrived.

Had I enjoyed myself, not looked at the analytics, and been patient, my list of about 100 recipients might have grown to something much larger by now. Or perhaps not, and instead I’d have an ongoing correspondence with the 50 remaining people who enjoyed reading my stuff from time to time, for years.

That doesn’t mean I should have kept it up, just that “it’s too late” was a bad reason, in 2013, to give up on a daily email newsletter. And analytics, always, are a bad reason to give up on art.

It’s popular to think we’re at the end of stuff. Maybe this is just a human impulse — apocalypse cults go back at least a couple of thousand years.

But how do motivations and expectations and hopes and work change if we’re in the middle, or even toward the beginning of some things?

We might still be in early capitalism.

There are companies valued at more than one trillion dollars now — those might be valued at ten trillion one day, and those valuations might not be wrong. (I’m not making a case either way on that, just that they are not certainly inflated.)

Despite just living through not only the hottest year on record, and the highest year-over-year increase in global temperatures, most climate forecasts are more optimistic now than they were ten and twenty years ago. We can expect a century of climate catastrophes, but almost certainly not a climate apocalypse.

2024 feels late to start a blog, but I bet in ten years now will seem like a great time to start.

It’s Too Late